This article was originally written for/published on MapCore.org

The following article contains quotes from interviews with Todd Papy, Design Director at Cloud Imperium Games, Geoffrey Smith, Lead Game Designer at Respawn Entertainment, Paul Haynes, Lead Level Designer at Deep Silver Dambuster Studios and Sten Huebler, Senior Level Designer at The Coalition. A big heartfelt ‘thank you’ goes out to these guys who took the time out of their busy schedules to answer my questions!

On the MapCore.org forums many amateur level designers ask for feedback on their portfolios or for advice on how to break into the games industry. But once you have signed your first contract and you have your foot in the door you will realize that this step marks merely the beginning of your journey. It is a winding path with many diverging branches and without much information available on the road ahead. This is the reason why I decided to interview professional designers in Senior, Lead or Director positions to share their personal experiences and advice with others trying to navigate this field. It is worth mentioning that the questions were not selected and phrased with the goal in mind to compile a ‘how to get promoted fast’ guide. Instead I wanted to give level designers insights into the careers of others – who have stood at the same crossroads before – in hopes that they get the information to pick the path that is right for them.

Hands-On VS Management

At the beginning of his career, Todd Papy started out as a “designer/environment artist” – a job title that dates back to times when team sizes were much smaller and one person could wear both hats at the same time. As the project complexity and team size grew, he specialized in level design at SONY Santa Monica and worked on the God of War titles. During his time there he moved up the ranks to Lead Level Designer, Design Director and eventually Game Director. From level design to directing a game – a career thanks to careful long-term planning and preparation? “It wasn’t even on my radar” says Todd. “I just wanted to build a game with the team and soak up as much information from the people around me as possible.”

So how do level designers feel who step into positions where the majority of their daily work suddenly consists of managing people and processes? Do they regret not doing enough hands-on-work anymore? Todd says he misses building and crafting something with his hands, but instead of going back to his roots, he decided to look at the issue from a fresh perspective: “As a Lead or Director, your personal daily and weekly satisfaction changes from pride in what you accomplished to pride in what the team has accomplished.“ Today Todd is designing the universe of ‘Star Citizen’ as Design Director at Cloud Imperium Games.

Geoffrey Smith – who created some of the most popular multiplayer maps in the Call of Duty and Titanfall series and who is now Lead of the ‘Multiplayer Geometry’ team at Respawn Entertainment – says his output of levels remains unchanged thus far, but he can “easily see how being so tied up with managing would cut into someone’s hands-on work”. Geoffrey calls for companies to provide the necessary training to employees new to management positions: “Managing people and projects is hard work and is normally a vastly different skill set than most of us in games have. Maybe that is why our industry has such problems with meeting deadlines and shipping bug-free games. A lot of guys work for a long time in their respective disciplines and after many years they get moved into a lead position. They certainly know their craft well enough to teach new guys but managing those guys and scheduling would be something brand new to them. Companies need to understand this and get them the training they need to be successful.” At Respawn Entertainment, the studio provides its department leads with training seminars, which helps the staff immensely, according to Geoffrey.

Sten Huebler, currently working as a Senior Level Designer at Microsoft-owned The Coalition, in Vancouver, says he definitely missed the hands-on work when he worked in a Lead capacity on ‘Crysis’ and ‘Crysis 2’: “I was longing for a more direct creative outlet again. That is why coming to The Coalition and working on Gears of War 4, I really wanted to be hands on again.” To Sten it was the right move because he enjoyed working directly on many of the levels in the game’s campaign and could then experience his fruit of labour with others close to him: “After Gears 4 shipped, playing through the campaign, through my levels with my brother in co-op was a blast and a highlight of my career. He actually still lives in Germany. Being able to reconnect with him, on the other side of globe, playing a game together I worked on…So cool!”

‘Gears of War 4’ developed by The Coaliation and published by Microsoft Studios

Paul Haynes, Lead Level Designer at Deep Silver Dambuster Studios, encourages designers to negotiate the amount of organizational tasks and hands-on work before being promoted into a position that makes you unhappy: “I always told myself that I wouldn’t take a Lead position unless it could be agreed that I retain some hands-on, creative responsibility, after all that’s where I consider my strongest attributes to lie. I agreed to both Lead positions (Cinematic/Level Design) under that principle – I never understood the concept of promoting someone who is good at a certain thing into a position where they potentially don’t get to do that thing anymore, as they spend all their time organising others to do it. So far I’ve managed to maintain that creativity to some degree, though I would imagine it’s never going to be quite the same as it used to be, as I do have a team to manage now. On the flip side though, being able to control and co-ordinate the level design vision for a project and having a team to support in fulfilling that is quite an exciting new experience for me, so not all the organisation and planning is unenjoyable.”

Specialization VS Broadening Skillsets

For the level designers who aren’t afraid of management-related tasks and who are willing to give up hands-on work for bigger creative control, what would the interviewees recommend: specialize and strengthen abilities as an expert in level design further or broaden one’s skillset (e.g. getting into system design, writing etc.)? Paul believes it doesn’t necessarily have to be one or the other: “I think it’s possible to do both (strengthening abilities and broadening skillsets) simultaneously, it would really depend on the individual involved. I would say that a good approach would be to start with the specialisation in your chosen field and then once you feel more comfortable with your day to day work under that specialisation, take on work that utilises different skillsets and experiment to see if you find anything else you enjoy.” He started out as a pure level designer but subsequently held roles that involved game and cinematic design at Codemasters, Crytek and Dambuster Studios. “I’ll always consider myself a level designer at heart”, says Paul, “though it’s been incredibly beneficial for me to gain an understanding of multiple other disciplines, as not only has it widened my personal skillset but it has enabled me to understand what those disciplines have to consider during their day to day job roles, and it has helped me to strengthen the bond with those departments and my level design department as a result.” This advice is echoed by Todd who encourages level designers to learn about the different disciplines as “that knowledge will help solve issues that arise when creating a level.”

‘Homefront: The Revolution’ developed by Dambuster Studios and published by Deep Silver

Sten also gained experience in related disciplines but ultimately decided to return to his passion and do level design. He explains: “It’s a good question and I feel I have been wondering about this myself regularly in my career. I think those priorities might change depending on your current situation, your age, your family situation, but also depending on the experience you gain in your particular field. (…) In my career, I was fortunate enough to try out different positions. For example, I was a Level Designer on Far Cry (PC), Lead Level Designer on Crysis 1 and Lead Game Designer on Crysis 2. Each position had different requirements and responsibilities. As a Lead Level Designer I was more exposed to the overall campaign planning and narrative for it, while on Crysis 2 I was more involved in the system design. However, my true passion is really on the level design side. I love creating places and spaces, taking the player on a cool adventure in a setting I am crafting. My skills and talents also seem to be best aligned on the level design side. I love the combination of art, design, scripting and storytelling that all come together when making levels for 1st or 3rd person games.”

Picking The Right Studio

As you can certainly tell by now, all of the interviewees have already made stops at different studios throughout their career. So each one of them has been in the situation of contemplating whether to pass on an offer or put down their signature on the dotted line. This brings up the question what makes them choose one development studio over the other? To Geoffrey it depends on what stage of your career you are in. “If you’re trying to just get into the industry for the first time, then cast your net wide and apply to a lot of places. However, ideally, someone should pick a studio that makes the types of games they love to play. Being happy and motivated to work every day is a powerful thing.”

This is a sentiment that is shared by all interviewees: the project and team are important aspects, but as they have advanced in their career other external factors have come into play: “It’s not just about me anymore, so the location, the city we are going to live in are equally important.” Sten says.

Paul is also cautious of moving across the globe for a new gig. “The type of games that the company produces and the potential quality of them is obviously quite important – as is the team that I’d be working with and their pedigree. More and more over the years though it’s become equally important to me to find that balance between work and life outside of it. Working on games and translating your hobby into a career is awesome, but it’s all for nothing if you can’t live the life you want around it.”

And it is not just about enjoying your leisure time with family and friends, but it will also reflect in your work according to Todd: “If my family is happy and enjoys where we live, it makes it a lot easier for me to concentrate on work.” He also makes another important point to consider if you are inclined to join a different studio solely based on the current project they are working on: “The culture of the studio is extremely important. I consider how the team and management work together, the vibe when walking around the studio, and the desk where I will sit. Projects will come and go, but the culture of the studio will be something that you deal with every day.”

‘Star Citizen’ developed and published by Cloud Imperium Games; screenshot by Petri Levälahti

But it goes the other way around, too: When it comes to staffing up a team of level designers, these are the things that Todd looks for in a candidate: “First and foremost, I look for level designers that can take a level through all of the different stages of development: idea generation, 2D layouts, 3D layouts, idea prototyping, scripting, tuning, and final hardening of the level. People that can think quickly about different ideas and their possible positive and negative impacts. They shouldn’t get too married to one idea, but if they feel strongly enough about that specific idea they will fight for it. People that approach problems differently than I do. I want people that think differently to help round out possible weaknesses that the team might have. People who will look for the simplest and clearest solution vs. trying to always add more and more complexity.“

For lead positions, it goes to show yet again how important a designer’s professional network is, as Todd for example only considers people that he already knows: “I try to promote designers to leads who are already on the team and have proven themselves. When I am building a new team, I hire people who I have had a personal working relationship before. Hiring people I have never worked with for such positions is simply too risky.”

Ups & Downs

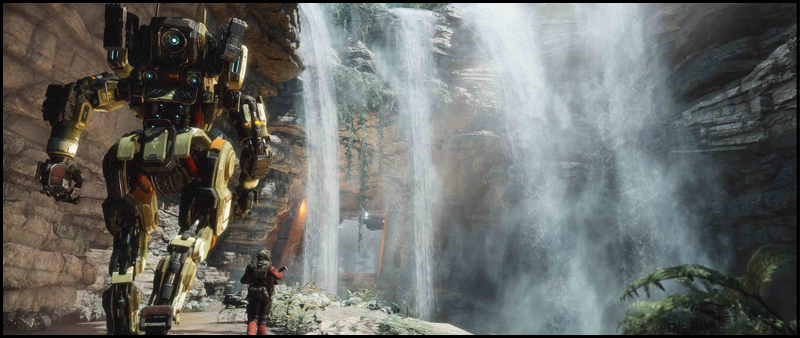

While the career paths of the designers I interviewed seem pretty straightforward in retrospect, it is important to note that their journeys had their ups and downs as well. For instance Geoffrey recalls a very nerve-wracking time during his career when he decided to leave Infinity Ward: “We had worked so hard to make Call of Duty a household name but every day more and more of our friends were leaving. At a certain point it just wasn’t the same company because the bulk of the people had left. The choice to leave or stay was even giving me heart palpitations. (…) After I left Infinity Ward, I started working at Respawn Entertainment and by work I mean – sitting in a big circle of chairs with not a stick of other furniture in the office – trying to figure out what to do as a company.” But he also remembers many joyful memories throughout his career: Little things like opening up the map file of multiplayer classic ‘mp_carentan’ for the first time or strangers on the street expressing their love in a game he had worked on. To him, shipping a game is a very joyful experience by itself and the recently released Titanfall 2 takes a special place for him. “The first Titanfall was a great game but we had so many issues going on behind the scenes it felt like we weren’t able to make the best game we were capable of. (…) After all the trials and tribulations of starting a new game company, Titanfall 2 is a game I am very proud to have worked on.”

‘Titanfall 2’ developed by Respawn Entertainment and published by Electronic Arts

As a response to the question of what some of the bigger surprises (good or bad) in his career have been thus far, Paul talks about the unexpected benefits of walking through fire during a project’s development and the lessons he learnt from that: “It surprised me how positively I ended up viewing the outcome of the last project I worked on (Homefront: The Revolution). I’d always thought I would aim to work on big, successful titles only, but I guess you don’t really know what’s going to be a success until it’s released. Obviously it was a disappointing process to be part of, and a lot of hard work and effort went into making it, despite the team always knowing that there were some deep lying flaws in the game that weren’t going to be ironed out. We managed to ride the storm of the Crytek financial issues in 2014, coming out on the other side with a mostly new team in place and yet we carried on regardless and managed to actually ship something at the end of it, which is an achievement in itself. I see the positives in the experience as being the lessons I learnt about what can go wrong in games production which stands me in good stead should I decide to take a more authoritative role somewhere down the line. Sometimes the best way to learn is through failure, and I don’t believe I’d be as well rounded as a developer without having experienced what I did on that project.”

Last Words Of Advice

At the end I asked the veterans if they had any pieces of advice they would like to share with less experienced designers. To finish this article I will quote these in unabbreviated form below:

Geoffrey: “I guess the biggest thing for guys coming from community mapping is figuring out if you want to be an Environment Artist or a Geo-based Designer and if you want to work on Single-Player or Multiplayer. Each has its own skills to learn. I think a lot of guys get into mapping for the visual side of things but some companies have the environment artists handle the bulk of that work. So figuring out if making the level look great is more enjoyable to you or thinking it up and laying it out is, will help determine which career you should follow. Other than that, just work hard and always look to improve!”

Todd: “BUILD, BUILD, BUILD. Have people play it, find out what they liked about it and what they didn’t. Build up a thick skin; people will not always like your ideas or levels. Try out new ideas constantly. What you think looks good on paper doesn’t always translate to 3D. Analyse other games, movies, books, art, etc. Discover what makes an idea or piece of art appeal to you and how you can use that in your craft.”

Paul: “The games industry is not your regular nine to five job, and everyone is different so it’s difficult to lay down precise markers for success. Different specialisations have different requirements and you can find your choices leading to different routes than your fellow team members. You need to make sure you carve your own path and try everything you can to achieve whatever your personal goals are within the role; success will come naturally as a result of that. You need to be honest with yourself and others, open to criticism and willing to accept change. I’ve seen potential in people over the years hindered by stubbornness, succeeding in the games industry is all about learning and constantly adapting. Also it’s important to keep seeing your work as an extension of a hobby, rather than a job. The moment it starts to feel like a means to an end, you need to change things up to get that passion back.”

Sten: “I always feel people should follow their passion. I firmly believe that people will always be the best, the most successful at something they love. Of course, it is a job and it pays your bills, but it’s also going to be something you are going to do for gazillions hours in your life, so better pick something you like doing.”

Friedrich Bode, 2017